Philosophy’s place in the national curriculum

Joint APT/BPA response to the call for evidence on the curriculum 2024.

Expanding the place of philosophy in education

We believe that there is room for a greatly expanded role for philosophy in the UK curriculum. (i) The Philosophy A level could grow substantially with some barriers removed. (ii) A Philosophy GCSE could make a valuable contribution to a broad and balanced curriculum by giving students a wider intellectual framework for integrating their cultural and scientific knowledge across many other subjects. (iii) Philosophy could play a valuable role at key stage 3 (and beyond) in supporting students’ education in British values. (iv) There is some recent worrying evidence of a decline in student engagement with the curriculum.1 As a highly engaging subject covering many long-lived and modern topics, philosophy captures students’ interest in the project of intellectual enquiry in general, given that it requires and enables students to consider vital and open questions and supports them in structuring their responses.

The Philosophy A Level

The A level is structured around four questions: How should I live? What can I know? Does the universe imply God’s existence? and What am I? The students cover the key philosophical traditions/texts answers to these questions from the early modern period up until now. The chance to engage with these vital, open and challenging questions makes philosophy highly engaging for students. The Philosophy A level however currently suffers from a low profile, increasing students and policy makers awareness of the A level is one of the key aims of the APT, as well as the upcoming British Philosophy Fortnight campaign, #PhilosophyMatters, coordinated by the BPA. It is notable that currently we are often absent from policy discussions because the Philosophy A level data is not broken out separately in JCQ reports, which we are trying to rectify.

Since the Philosophy A level was introduced in its current form in 2016 it has rated consistently in the top five A levels for difficulty. This reflects the substantial jump in the level of rigour and logical clarity demanded of the students’ writing. Despite this the A level has grown substantially since 2016 from 2000 summer exam entries to just under 4000 today. The two barriers to its further growth are (i) the grade profile imposed upon it is too ungenerous and therefore unfair compared to subjects with cognate content. (ii) The lack of a qualification pathway for philosophy teachers.

Philosophy GCSE rationale

There is a large gap between the breadth and density of the cultural capital that students who attend independent schools attain and the cultural knowledge obtained by students in the state sector. One reason for this gap is that the national curriculum does not cover the longer time horizons of human history, this means that students lack an overall schema into which broader cultural knowledge could be integrated.

This leads to a Balkanization of knowledge, where students have knowledge of particular periods of history but lack an understanding of where these periods fit in the wider sweep of history, where they understand areas of scientific knowledge without having an overall sense of the project of scientific enquiry itself and the place of different sciences within it.

Philosophy studies the history of how human communities have understood their universe, themselves and their society. Philosophy inducts students into these (still live) questions of the nature of reality, of human consciousness, ethical conduct and just political society by orienting them in the long historical sweep of philosophical debates on these questions. As such philosophy offers ‘powerful knowledge’, knowledge that allows students to build schemas into which large areas of cultural and scientific understanding can be ordered.

One of the key course aims of an oft-mooted Philosophy GCSE is that by end of the course the students should have studied philosophical arguments which give them an understanding of the broad overall timeline of the history of humans’ understanding of their cosmos, themselves and their society – ordered into 3 periods

– 500 BC – 500 AD understanding of cosmos, humans and society in the classical age and its development from earlier mythological understandings of the universe

– 500 AD – 1500 understanding of cosmos, humans and society in Christian and the Islamic worlds

– 1500 – Present – understanding of development of modern scientific understanding of cosmos humans and society

Another key aim is to give students the chance to apply the techniques of philosophical argumentation they learn through studying these thinkers to vital open contemporary questions in discussion, to engage them in thinking for themselves and each other in determining their stance on these open questions. (e.g. free speech, animals and the environment, the philosophy and ethics of AI, democracy).

Philosophy at key stage 3

Recent research has uncovered substantial issues with democratic education in schools “Utilising a survey of 3000+ secondary school teachers and detailed analysis of policy documents, this article shows

(1) the promotion of democracy is largely neglected by education policy, (2) schools are offering scant provision vis-à-vis democratic education and (3) the majority of teachers feel fundamentally underprepared to teach about democracy.”2 As outlined in the article and certainly in agreement with many colleagues’ experiences as teachers, the teaching of British values could be improved substantially. This is for structural reasons: they are simply given to students as straight principles, without enough intellectual context or reasoning, and they are not discussed often enough in activities with conviction. This is a missed opportunity for many reasons. The intellectual history from which belief in democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty, mutual respect and tolerance of those of different faiths and beliefs emerged is in large part Britain’s own history since the 19th Century. Philosophy teachers would have both the expertise to teach the substance and significance behind our commitment to these values as well as the skills to guide students to exhibit independence, freedom of thought, and critical thinking in their discussions, practising some of the key democratic virtues these values are intended to allow to flourish

.

Philosophy and Critical Thinking

Philosophy has also been underused as a subject given its role in developing critical thinking: Philosophical thinking and methodology can be used across many or all other subjects. Philosophy promotes the skill of understanding arguments in their parts and logical relations, as well as flexibility of thought. This reflects the position philosophy has at tertiary level, where many subjects also necessarily include a philosophical component, most usually on reasoning, epistemology or ethics.

Given the real difficulties even well-informed adults have navigating the digital maelstrom of information now presented across social media, it is imperative that our young people are equipped at least with a basic grasp of the character of good reasoning and how to judge the epistemic weight of different claims for themselves.

Philosophy’s place on the curriculum

At present Philosophical arguments are largely encountered by students only in the context of religious education. This hinders the teaching of philosophy both by severely limiting the elements of it which can be taught and by preventing these arguments being presented within the framework of a distinctively philosophical approach. In the context of a religious studies lesson both the characteristic epistemic position of philosophy and its insistence on logical rigour are not taken as primary, which deprives philosophical arguments of their force and import.

Economic and Geographic injustice of Philosophy provision

The current profile of the centres which offer students the opportunity to study philosophy is disproportionately skewed towards independent schools and schools and sixth form colleges in more affluent areas. This leads to an injustice in both the economic and geographic distribution of students’ opportunity to engage with Philosophy.

In terms of economic justice the data we have gathered indicates that independent schools almost always include some form of philosophy provision in their curriculum. This often runs throughout the key stage 3 to A level. Independent schools who do not offer the philosophy A level are most likely to offer the OCR Religious Studies A level which is the exam board closest in content and approach to philosophy (over 50 % cognate content).

There are also substantial geographic disparities in students’ ability to access philosophy. No more than 250 state schools offer the philosophy A level and although we are in early stages of Philosophy A level centre census data gathering, the current results indicate these are distributed more densely in London and the south-east of England. A further illustration of the disparity in philosophy provision comes from multi-academy trusts. Mr Stephen Law, a Regional Director at United Learning Trust informed us that out of their 60+ schools only 1 offers the Philosophy A level. In this regard it’s important to underline that this lack of access to philosophy also extends even to the access to philosophical arguments students have through the RS A level. Only 18% of united learning trust schools even offer religious studies.

R Penney – One memory repeated throughout my time as head of philosophy at St Dominic’s Sixth Form College was asking the students, ‘have you heard of.. x’ (always some substantial intellectual figure like Aristotle), – the answer was always no – and at one time accompanied by the plaintive, ‘we’re just 16 years olds from Harrow, why would we know who x is?’. This student had a point, why would she know, unless someone had taught her. Many students in the UK currently will have no opportunity to learn who Socrates, Plato and Aristotle were, let alone have the chance to engage with the existential questions they asked of themselves, others and their own society. This is despite the fact that Britain has a long and substantial philosophical tradition of its own, many of whose works and philosophies underpin the British Values taught in our schools and colleges.

Philosophy and inclusion

Philosophy is an inclusive subject because it is accessible to all and builds students’ self confidence in debate and their oracy skills more generally. The key strengths of philosophy as an academic discipline in developing students’ oracy is through giving students confidence in being able to articulate seemingly complex ideas in a simple fashion. Philosophy teaches students to order their thoughts, going from one idea or claim to the next in a clear and reasoned manner, in order to convey an overall argument, idea or vision to an audience.

As a practical, discursive subject which encourages students to talk through problems and opposing positions, philosophy also develops students’ oracy by giving them an open space of debate in which they can freely develop their own thoughts. Numerous studies, including the most recent EEF evaluation of PC4 as well as other international studies, have shown the positive impact of philosophy teaching, such as improvements in students’ self-confidence as well as the softer skills and mutual respect necessary to conducting good philosophical discussions. The observed improvement was even larger for EAL and Send students.

Development of oracy

Philosophy is uniquely well suited to developing students’ oracy skills, both as an academic and practical, discursive subject.

The key strengths of philosophy as an academic discipline in developing students’ oracy is through giving students confidence in being able to articulate seemingly complex ideas in a simple fashion. Philosophy teaches students to order their thoughts, going from one idea or claim to the next in a clear and reasoned manner, in order to convey an overall argument, idea or vision to an audience.

As a practical, discursive subject which encourages students to talk through problems and opposing positions, philosophy also develops students’ oracy by giving them an open space of debate in which they can freely develop their own thoughts. Numerous studies, including the most recent EEF evaluation of PC4 as well as other international studies have shown the positive impact of philosophy teaching, such as improvements in students self-confidence as well as the softer skills and mutual respect necessary to conducting good philosophical discussions. The observed improvement was even larger for EAL and Send students. temporary questions in discussion, to engage them in thinking for themselves and with each other in determining their stance on these open questions.

Academic and practical development

As an academic subject philosophy exercises students’ minds by asking them to think with the broadest possible scope, at a consistently high level of abstraction, and with consistent logical precision. As the German Philosopher Humbolt wrote in his report on the place of philosophy in German universities “A sharp knife can cut anything”. The skills philosophy develops in grasping the intellectual structure of problems also make philosophy a uniquely practical subject.

This is reflected in employer’s attitude towards Philosophy graduates, this quote from a tech CEO in The Wall Street Journal is a good example – While we’ve hired many computer-science majors that have been critical team members, It’s non computer science degree holders who can see the forest through the trees. For example, our chief operating officer is a brilliant, self-taught engineer with a degree in philosophy from the University of Chicago. He has risen above the code to lead a team that is competitive globally. His determination and critical-thinking skills empower him to leverage the power of technology without getting bogged down by it.4– Just because it teaches students to think at high levels of abstraction, philosophy is, despite its reputation, a very practical subject: in short, philosophy encourages hard thought about many issues facing us every day. Philosophers have made important contributions to modelling in the social sciences, to the development of computer technology and AI, to legal ideas that have real-world, everyday consequences.

Knowledge of philosophy’s thinkers and traditions allows the students to locate themselves in the longer time horizons of intellectual history, which in turn forms a framework within which their cultural understanding can expand.

Intellectual and character development

Philosophy also has a key role to play in the intellectual development of students. As an activity, both the substantial uptake of PC4 in the UK as well as the success of even more ambitious programmes like Ireland5 show the positive impact on students well-being and intellectual development of the collective class activity of open philosophical debate.6 One interpretation of the impressive impact of these programmes is the centrality of intellectual agency in the experience of self worth. Intellectual agency is something that needs to be practised, it needs to be placed in a context in which it has the chance to be exercised. The key point about a philosophical debate is that it starts from the premise that we do not know, that the best we can do is grasp the matter in thought as best we can, this lack of a determined or authoritative answer allows the students freedom to exercise their own intellect.

Philosophy and Computer Science

Philosophy and computer science have a common foundational discipline, formal logic. The skills involved in understanding how to create a deductively valid argument are interchangeable with the skills to write and execute a computer programme. Familiarity with logical notation is also very closely equivalent to understanding operators in programming languages. The recent Royal Society report on the state of computing education7 notes that a key issue which puts students off computer science qualifications is the perceived difficulty of writing code. Learning the logic foundations of code can serve to demystify the subject.

The need for students to have a keen grasp on logical argumentation has grown for a number of reasons; the impact of AI will mean that students will need to understand the probabilistic character of the operations of AI system in evaluating their output and applicability as well as being able to identify any logical fallacies or inconsistencies in AI output which are the result of hallucination, secondly there is both an increasing trend of attraction to conspiracy theories as well as accompanying technological trends which make reliable identification of sources challenging, in this context philosophy provides students with the tools to take a critical distance to claims and independently evaluate their plausibility given their understanding of what the claims truth would imply, rather than relying only on the claims’ source.

Philosophy Short form A Level

If there are to be significant changes to A Level provision is structure and form – i.e. something akin to the oft-mooted British Bacc – then a Year 12 award in ‘Philosophy, Ethics and Reasoning’ would be an promising and excellent foundation for students whether they are further interested in STEM subjects or in art and humanities subjects, as well as providing a training in thinking that will be good for many students in their chosen employment in the future. Such a course would then lead to more material in Year 13 for a full award. It might also sit as a ‘core’ subject, if it is planned that students pick one or two cores from a small family of options. As above, philosophy has the ability to marry and reach across many subjects from any standard curriculum.

The teacher pipeline.

There is a clear precedent both in the previous Labour Government’s introduction of Citizenship and in the Conservative’s programme of expanding Classics education that the introduction/expansion of the place of a subject on the curriculum can draw new candidates into the teaching profession. Since this opportunity to teach their subject was particularly attractive to those who excelled in their studies in both cases it is highly probable that these new teachers attracted into teaching had attained higher degree classifications at better ranked institutions than the average ITT applicant.

A similar logic applies to the case of Philosophy. There is a pre-existing pool of graduates who have excelled in Philosophy, love their subject but have never seen any opportunity to teach it in English and Welsh schools. This is largely due to the fact that philosophy is only ever taught until the KS5 level as part of RS. This presents a barrier to many if not most Philosophy graduates who would consider teaching, they would be enthusiastic at the chance to become Philosophy teachers, but find that religious studies is substantially a different subject.

Due to a combination of declining student interest in RS and the low availability of the Philosophy A level there are a large number of Philosophy ‘cold spots’, areas in which students have almost no access to philosophy. Despite this lack of provision, the continuing demand is evidenced by the work of the Royal Institute of Philosophy who fund philosophy workshops for over 60 schools each year.

The chair of Harris City Academy Crystal Palace Governors, Ms Angela Kail, has also reported to us that they had attempted to start teaching philosophy but had not been able to recruit a philosophy teacher. We are unable to access any further data on whether other multi-academy trusts are in a similar position but it seems possible the Harris Federation is representative here.

There is currently no way to qualify as a Philosophy teacher in the UK. In the medium term establishing Philosophy as a viable subject and attracting new teachers would involve developing both a Philosophy GCSE as well as an accredited Philosophy ITT course in parallel. Both of these introduce a substantial lead time so there is a place for a short term strategy to train Philosophy teachers on the job.

Currently the most substantial centres of excellence in Philosophy teaching are in Sixth form colleges. There are a number of colleges with large departments and excellent attainment records who could be part of training up new teachers in partnership with multi-academy trusts if given institutional support and funding.

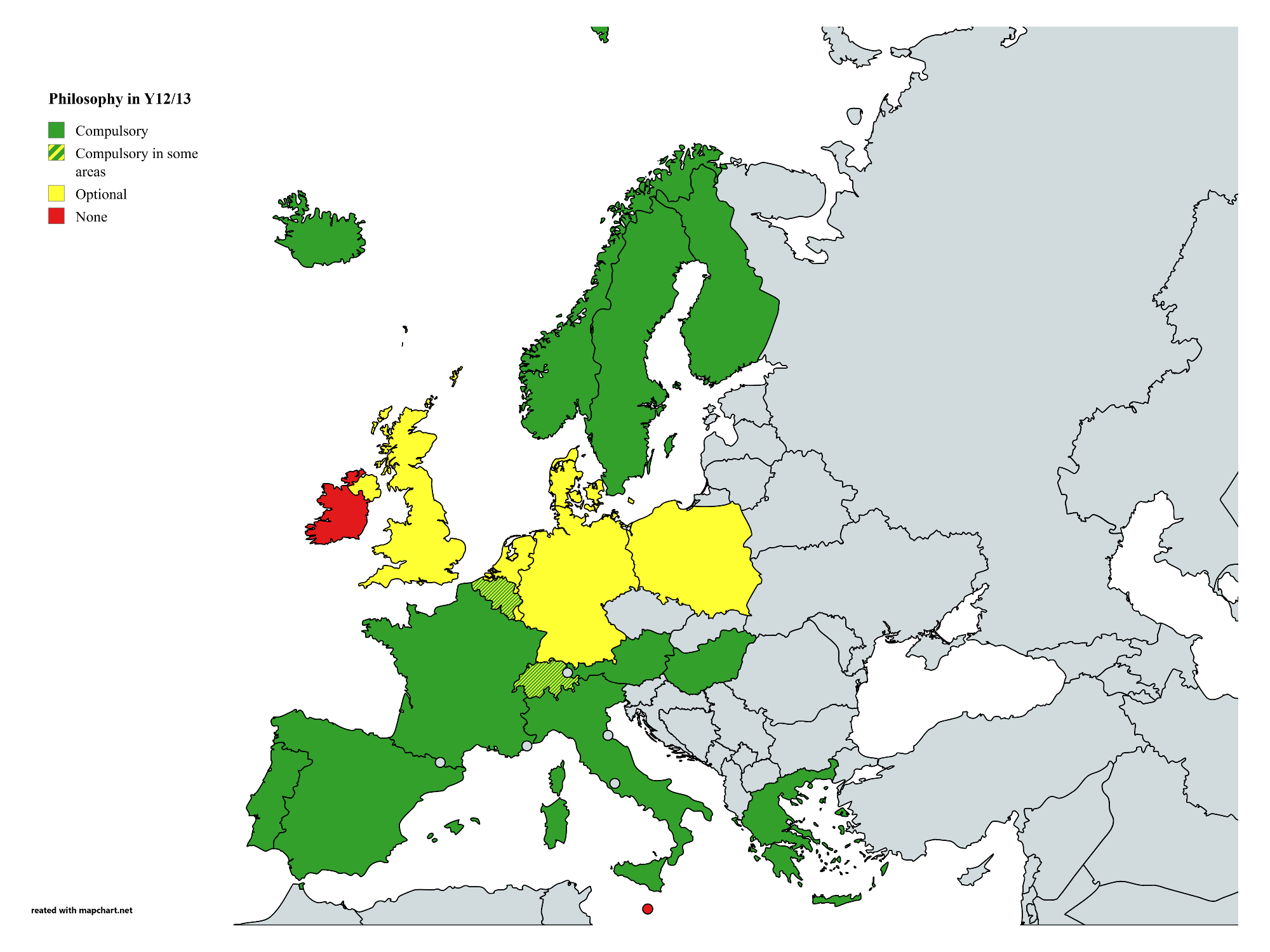

The International comparison

As compared to our European peers Philosophy has comparatively little space on the curriculum. Although we are similar to France, Germany and some other northern european countries in offering philosophy as a voluntary subject at year 12 and 13 philosophy is offered in far fewer schools in England and Wales than these European countries.8

| Country | Y12 Philosophy Y13 Philosophy |

| UK |

Optional (A-Level) Compulsory (IB theory of knowledge) |

| Ireland | None (LC only RE) None (LC only RE) |

| France |

Optional (baccalauréat général ‘humanities, literature, and philosophy’) Compulsory (baccalauréat général 3h ‘philosophy’) |

| Germany | Optional (Abitur ‘philosophy’ or ‘ethics’) |

| Austria | Compulsory (Matura 2h ‘psychology and philosophy’) |

| Switzerland | Varies (cantons can offer as Matura basic subject e.g. Lucerne) |

| Luxembourg | Optional (diploma ‘humanities and social sciences’) |

| Spain | Compulsory (bachillerato ‘philosophy’) |

| Portugal | Compulsory (diploma/certificate 2.5h ‘philosophy’) |

| Italy | Compulsory (maturità 2-3h ‘philosophy’) |

| Netherlands | Optional (VMBO/HAVO/VWO diploma) |

| Belgium (Flemish community) | Compulsory (certificate ‘philosophy of life’) |

|

Belgium (French and German communities) |

Semi-compulsory (certificate 2h of ‘philosophy and citizenship’ or ‘ethics’ unless ‘religion’ taken) |

| Denmark | Optional (STX/HTX/ HHX ‘philosophy’) |

| Norway | Compulsory (‘religion and ethics’ and philosophical elements of ‘social science’) |

| Sweden | Compulsory (‘philosophy’ part of ‘social science’ subject) |

| Finland | Compulsory (certificate ‘philosophy’) |

| Iceland | Compulsory (philosophical elements of ‘social science’) |

| Poland | Optional (maturity certificate) |

| Hungary | Compulsory (‘ethics’) |

| Malta | None (SEC only RE) |

| Greece | Compulsory (apolytirio 2h ‘philosophy’) |